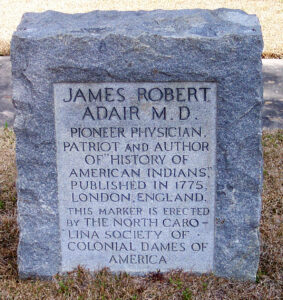

For nearly 70 years a granite monument stood at the intersection of U.S. 501 and N.C. 710 on the outskirts of Rowland. The monument honored Dr. James Robert Adair – physician, patriot, Indian trader and author.

Monument ceremony

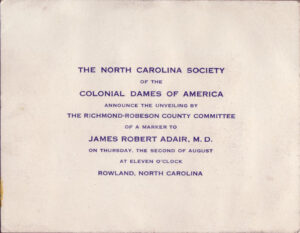

The hot summer sun beat down on August 2, 1934 as the Robeson-Richmond Committee of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America placed the granite monument to the memory of Adair.

The committee’s president, Mrs. N.A. McLean, presided over the events before a crowd of more than 500. Mary Harllee and Jane Alford, descendants of Adair, were chosen to unveil the monument. Dr. A.R. Newsome, secretary of the State Historical Commission, accepted the monument on behalf of the state. Special guests were Gov. and Mrs. A.W. McLean; Col. and Mrs. W. Chauncey Alford; Col. William Curry Harllee; Brigadier General Manus McClosky, commander of Fort Bragg; Dr. Paul P. McCain, head of State Tubercular Sanatorium; and Wiley McNair, a New Orleans riverboat captain.

Before the unveiling everyone gathered in Ashpole Presbyterian Church where they were addressed by Newsome, McCain, Col. Harllee, McClosky and C.J. McCallum, elder of the church. Gen. McClosky spoke fondly of Harllee with whom he served in Cuba, the Philippines and China throughout World War I.

McClosky went on to say he felt a common tie with Adair, since he also was Scotch-Irish and North Carolina was his adopted home. He said that Adair “made a plea for preparedness, warning against impractical dreamers who believed war could be avoided by treaties. The greatest cost of war is not in lives, money or the consequent economic upheaval, but in the widows and orphans and others who are bereaved.”

The Rowland Garden Club cared for the monument for years. About eight years ago the Colonial Dames were approached about having the monument moved from the intersection. Plans were discussed and it was hoped that the state highway department would relocate the monument. This was not to be and due to the efforts of many individuals it is located now beside the front entrance of Ashpole Presbyterian Church.

Adair’s life

Adair was born about 1709 in Ireland and migrated to Pennsylvania in 1730 with his father and brothers. In 1735, he was a business partner with Indian trader George Galphin in Charleston, S.C. His first trading was with the Catawbas and Cherokees but he later enlarged his area to cover trade with the Choctaws and Chickasaws

He settled with his first wife on a plantation called Fairfields in present-day Greene County. By 1770, he settled on plantation Patcherly near Rowland with his second wife.

He was father of John Adair, who married Jennie Kilgore; Edward Adair, who married Elizabeth Martin; Sara Anna Adair, who married William McTyer; Elizabeth Hobson Adair, who married John Cade; and Agnes Adair, who married John Gibson.

At the age of 65 he answered the call to join the patriots’ cause against Great Britain by joining General Francis Marion. He served as medical officer on the general’s staff.

Time with American Indians

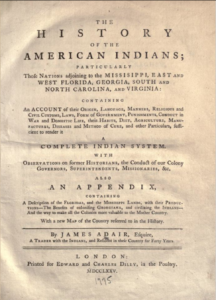

In 1775 Adair’s book, “The History of the American Indians; particularly those nations adjoining to the Mississippi, East and West Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, and Virginia,” was published in London. He had received a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin to a leading London publishing house.

Adair’s memoirs show the life of a backcountry trader and the daily interactions with the American Indians. Adair presents the history and culture of the Catawba, Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw Indians he gathered from more than 40 years among them.

This publication offered the most complete look at the Indians and was eagerly accepted by policymakers, diplomats and scholars. It became easier to work with them by knowing more about their laws, government, religion and domestic life.

Adair became embattled in a political tug-of-war with the French in trying to entice the Choctaw Indians to break alliance ties with them and side with the British. This was encouraged by South Carolina Gov. James Glen. But the Choctaw people were divided in where their loyalty lay and the result was a bitter civil war among tribal members.

Problems also arose because Glen and his friends saw this as a chance to increase their personal fortunes. At the end of King George’s War (1744–48), Adair visited the French at Fort Toulouse. It was reported that he had joined the enemy when in fact he was arrested and faced the possibility of hanging.

He managed to escape and returned to his efforts of persevering the Indian history and culture. The Indian war of 1760-61 found him again going against the French when he was commissioned as a captain to a band of Chickasaws.

A major thesis of his book that is not widely accepted any longer is his 23 arguments to demonstrate that the American Indians were of Hebrew descent and the Lost Tribes of Israel. Many agreed at the time that the Indians might be descendants of the ancient Jews. The theory was not only accepted by Elias Boudinot, president of the Continental Congress, but expanded in his own book, “Star in the West, or An Attempt to Discover the Long-lost Tribes of Israel,” published in 1816.

His descendants

Adair’s descendants have numbered in the thousands and have spread out from Robeson County to all points of the world. They have become soldiers serving in all wars, farmers, business leaders and teachers. Some of his descendants who have gained national attention are Hugh McCall, former CEO of Bank of America; and Malcom McLean, founder of McLean Trucking, Sea-Land Company and Trailer Bridge.

Sources: Adair, James. “The History of the American Indian”; The Robesonian August 6, 1934; Harllee, William Curry. “Kinfolks”; and The Encyclopedia of Alabama.