It doesn’t matter if you call it Drowning Creek, Lumber River or the Old Lumbee the dark waters that wind through Moore, Scotland and Robeson Counties draws you in almost hypnotizing you. In the early years of the county the river served as a highway for commerce. Trees harvested in the county were rafted down the river to the Little Pee Dee and on to Georgetown, SC.

When I think of the Lumber River, I think of the first lines of Lord Byron’s poem “She Walks in Beauty”

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes

Over the years pen has been put to paper to capture the river in poetry the most notable from the first four decades of the 1900s are William Laurie Hill, Woodberry Lennon, Clara Johnson Marley and John Charles McNeill.

Dr. William Laurie Hill

Hill was born March 29, 1835 in Maxton, NC to William R. Hill and Sarah Simmons Hill. He was brother of Rev. Halbert G. Hill, long time pastor of the Maxton Presbyterian and Center Presbyterian Churches. The brothers’ book “Blue Bird Songs of Hope and Joy” was marketed as a collection of songs that are like a breath of spring from out Southland. William was referred to as the poet laurate of the North Carolina Press Association Editor of “Our Fatherless one” the newsletter of Barium Springs Presbyterian Orphanage. He died in November 1921 at the age of 86 and is buried in the Centre Presbyterian Church Cemetery, Maxton, NC. His poem Old Lumber River was printed in the January 16, 1908 issue of The Charlotte Observer.

Old Lumber River

Yes, thou art old. and generations past.

The Red man’s home was in thy forest’s vast.

Along thy current shot his swift canoe –

He knew each cove, and vapid-swamp and slough.

And in thy swamps, did he the wild game chase.

And in thy swamp, did he the wild game chase.

Arts of the finny tribe, he wisely knew –

And many well rewarded casts he threw.

Alone with nature dwelt these Redman there –

Hunting their game, the ‘possum, deer and bear –

While for some fancied cause, in vengeful wrath.

Their council held; they strike the dread war-path.

Years pass – and now we see the Scotch-man come,

To build along thy banks a thrifty home –

The Redman sees with awe, great clearing made

Upon the sandhills sloping to the glade.

The hunting grounds, now yield crops of maize –

And sheep and cattle in new pastures graze –

Before the woodman’s ax, the Redman flee,

Seeking some spot where white men may not be.

Vain hope! for savage men must now give place

To men of brawn, and brain, a sturdy race.

The poor Indian fades from mortal view –

No more to seek this haunt, that once he knew.

In all these changes. Lumber River flows

Her quiet way! And as each season goes

More people settle on her thrifty sod.

Rear homes and alters for Almighty God.

Flow gentle river, onward to the sea.

The good folk on try banks are loving thee.

True men and sages on thy sandhills dwell –

Not would some highland home suit them as well.

A son of thine, oft sweetly sung of the three,

And now he sleeps by creeping vine and tree

He lov’d so well: and thou shall hear no more –

The magic cadence of his skillful oar,

No more will he of “Lumber River” sing.

No more his soulful voice shall tell of spring

Along thy banks; or in thy “bonnie braes,”

Or charm us, with his sweet “October days.”

But now, as thou art flowing to the sea.

Thy voice is gently whispering to me.

Of him who sung those songs to nature true.

Songs rich with sympathy, and ever new.

Old River, ever dear to him – to me.

We loved thy lily pads, and every tree

Along they shady banks, nor would we sleep.

Where thou couldst – not o’er us thy vigil keep.

William Laurie Hill

Floral Manse, January 14th, 1908

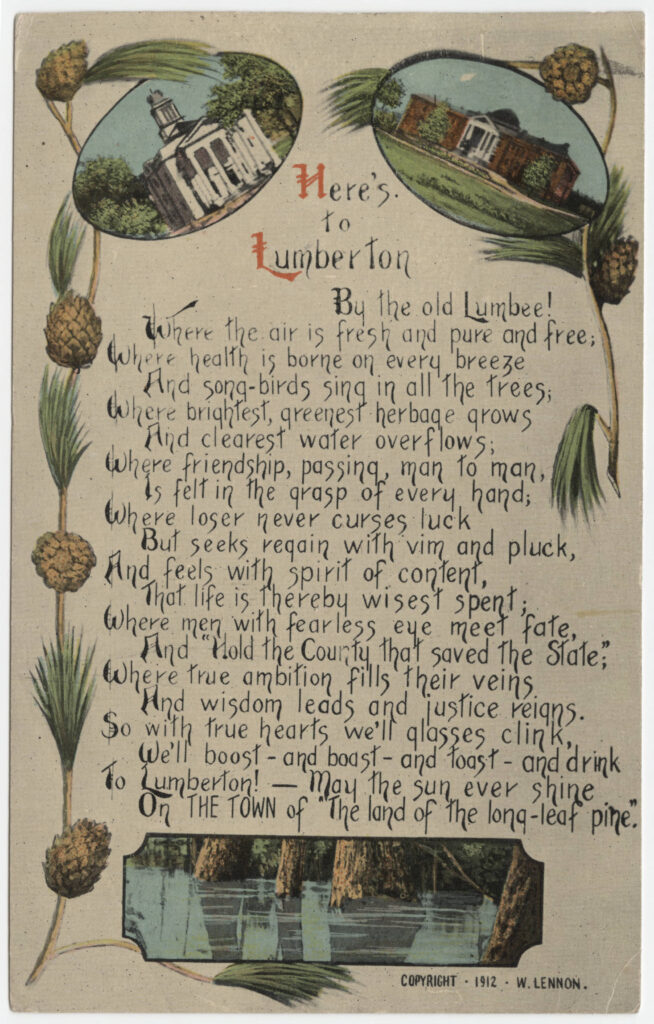

Woodberry Lennon

Lennon was born January 16. 1885 in Columbus county, son of the Frances and Sue Lennon. The family moved to Robeson County shortly after his birth and he lived practically all his life in Lumberton. He graduated from Wake Forest College in 1907, completing his law course at the same time. He served as deputy clerk of Superior Court, solicitor of the recorder’s court and for a short time as recorder. For most of his legal career he practiced law alone but for a short time was in partnership with Horace Stacy, Sr.

From his obituary in The Robesonian February 12, 1923 “Woody, as he was known to practically everyone here and to a large number throughout the state, was a genius at map drawing, as is evidenced by his extraordinary good map of Robeson county, made last year. Not only is it a credit to Mr. Lennon, but to the county itself. If he had an enemy it is not known. In his early manhood he showed his ability for handling complex things and was appointed deputy to the clerk of the Superior Court of Robeson county. Many legal problems were solved by Mr. Lennon while he was attorney for the town of Lumberton. In many instances he was a very valuable asset to the town and during the time he was thus employed the authorities and town fathers knew that their guidance in affairs was being well handled by the young lawyer.”

The Sunday after his death Dr. Charles Henry Durham pastor of Lumberton First Baptist Church spoke from the pulpit about Lennon. In Durham’s words Lennon was an active part of all the work of the church and that his place would never be filled. He was especially faithful to the preparation of the musical programs. He not only sang but also played the violin. Durham went on that “while we miss him today in our own choir here, we know that he is filling his place for the first time in the heavenly choir along with the angels in glory.” Durham also urged the younger members of town to step into the ranks, fill in their places, complete the work so nobly begun and emulate his example.

Lennon’s poem “Here’s to Lumberton” first appeared in a special issue of The Robesonian on October 19, 1911. The newspaper referred to Lennon as the Bard of Robeson. He died in 1923 at the age of 38. He was sick only a week, death being due to pneumonia following influenza.

Clare Johnson Marley

Clare Johnson was born 1896 in Moore County, North Carolina but moved to Lumberton to attend school and be near her brother, Dr. Thomas C. Johnson who operated the Thomson Hospital after the death of Dr. Thompson. She lived with her sister Mrs. J.R. Poole on Water Street within sight of the Lumber River. After graduating from Flora Macdonald College, she began her 44-year teaching career in Lumber Bridge where she met her future husband. In 1917 she married Walter Ellis Marley, and they were parents of Margaret Modlin, Rebecca Moore, Morris Stephens and Walter Ellis Marley, Jr.

She received her Master of Arts degree in Dramatic Art from University of North Carolina. Her love for playwriting came from her time with Dr. Frederick H. Koch, Founder and Director of the Carolina Playmakers. Her love for plays led her to write several plays based on North Carolina Historical events. Her works are persevered a n the Southern Historical Collection at UNC. Several of her plays written while a student at UNC were produced by the Carolina Playmakers: Swamp Outlaw, about the notorious “North Carolina Robin Hood,” Henry Berry Lowry; The Old Dram Tree, her first play of the Crusoe Island folk; Flora Macdonald, the highland girl who risked her life to save Bonnie Prince Charlie; Crusoe Islanders, a tragic drama of the Carolina Low Country; The Wraith of Chimney Rock, a play in verse, drawn from a legend, still cherished by the hill folk of the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina.

Mary Slocumb, a play in poetic prose about the North Carolina heroine of Moore’s Creek Battle between the Whigs and Tories, was produced at Chapel Hill in the Twentieth Annual Festival, 1943. Swamp Outlaw was published in the Carolina Play-Book in March 1940; The Old Dram Tree was published in Edgar Allan Poe’s Literary Messenger, in August 1942; Swamp Outlaw was included in The Players Magazine, The Educational Theatre in America, in May 1943.

Marley twice won the Sidney Lanier Cup for Playwriting, in 1943, for Flora Macdonald; and in 1944, for The Old Dram Tree. Many colleges, high schools, clubs and festivals preformed her plays over the year. A citation of honor, The Roland Holt Silver Cup for Playwriting, was awarded Clare Johnson Marley at the Carolina Playmakers Theatre by Professor Samuel Selden, Head of the Department of Dramatic Art, University of North Carolina, for outstanding work in graduate playwriting while working for her Master of Arts degree.

Her tribute to the Lumbee was published in the 1954-1955 National Poetry Anthology by Librarians and Teachers of the National Poetry Association.

Ever Onward Rolls the Lumbee

Ever Onward Rolls the Lumbee …*

‘Tis a serpent long, winding sluggishly

Through dense labyrinths of vines

And lowland mosses …

Dark and treacherous

With black waters rolling onward …

Ever onward toward the sea,

Countless whirlpools whirling

Restless quicksands sucking,

Green water snakes breaking the water …

Appearing and disappearing in capers turbulent …

Black water bugs darting here and there,

Long trailing mosses streaming out

From the limbs of gnarled Cypress trees,

Lacy junipers and venerable water oaks

Like an old man’s gray beard

In the frolicsome wind …

Marsh ducks feeding in the crab grasses

Along the water’s edge …

Wild geese flying southward,

Dark waters slapping the low banks,

A crane standing on one foot

Sleeping in the fading sunshine …

Churning waters.

Bull alligators fighting

Over the antiered stag

Trapper and struggling in quicksands

At the river’s edge.

The musical chirping of birds …

Bluebirds, cardinals, sparrows and thrush …

Foreboding hoots of an owl,

Screaming of the wildcat

On the track of the prey,

And the rushing of the wild boar

Through crackling sword grasses.

A crude raft of logs drifting down the river

Carrying two Croatans** sleeping

By wooden keys filled with moonshine***

Taken from a still

Hidden in the hollow of a giant oak

And loaded by the light of the moon …

Alligators slide down slimy banks

And follow the raft that rifts

On black waters that roll onward

Through dismal swamps,

Sea marches green,

Black waters of the Lumbee River

That move onward …

Ever onward toward the sea.

Footnotes to the poem by Marley – *Lumbee River is a deep, winding and treacherous river in Robeson County, NC, **Croatans are Indians located in Robeson County and said to be the descendants of the Lost Colony that amalgamated with the Croatans when Governor John White failed to return with his ship of supplies 1589, ***Moonshine is illicitly distilled liquor.

John Charles McNeill

One of the most loved poets that wrote about the Lumber River was John Charles McNeill. For the life of McNeill, I call on the 1991 writings of Richard Walser and the 1949 biographical sketch by Agatha Boyd Adams printed by UNC Press.

McNeill the youngest child of Captain Duncan and Euphenia Livingston McNeill was born July 24, 1874 at his father’s farm Ellerslie near Wagram., his father’s farm near Wagram in Richmond (later Scotland) County. John Charles had three sisters and a brother: Mary Catherine (Mrs. Jasper Lutterbok Memory), Ella (Mrs. Daniel A. Watson), Wayne Leland, and Donna.

His father in addition to farming had been at various times an editor, lecturer and writer. His mother was described as a woman of unusual beauty and of forceful character. The deep impression which she made on her poet son is evident in the many references to mothers and motherhood throughout his writing.

His father recalled that John Charles “from boyhood was delicate in his appetite. The

table might be loaded with luxuries, but he would choose only bread and milk, with butter and dainty fruits, not taking meats.” Perhaps a doctor might discover in this limited diet for a growing active boy one of the causes of the tragic illness of his early manhood. In spite, however of his dainty appetite and bookish tastes, he grew up strong and vigorous; “tall, slender, and beautiful in form and feature,” his father described him.

He had the freedom of the woods, the creeks and river, and the endlessly fascinating swamps, with their great variety of bird and insect and animal life. By his own witness, he was very early filled with that love of the outdoor world which never left him:

“The first thing I remember of this world or of any world, for that matter is the being lifted up by a big boy in a cadet uniform to get a peep of four blue eggs in a hollow. The big boy explained how they were bluebird eggs, how the bluebird’s noggin was not hard enough nor his bill enough like a chisel for him to dig out a hole for himself, and how he waited until the sapsucker had made and abandoned the nest, when he, the bluebird, moved in and took charge. I don’t know when George III died, but I know when that stump fell; will never forget where it stood nor the day, which now seems a thousand years gone, when I gazed with wonder at those eggs.”

McNeill’s boyhood was not a solitary one. He became a leader among the neighborhood boys, “the sunburnt boys,” as he later named them in his rhymes. He excelled in running, jumping, rowing and swimming; he knew to the full the cool delight of diving from “the springboard

extended over the old deep swimming hole and watching the mellow bugs on the surface scattered by plunging naked bodies.” He built boats to use on the river, one called “The Wild Irishman,” another “The Nereid.” The river and the nearby swamps and woods were as truly his home as the big farmhouse of his father, and to them he loved to return in memory and in writing.

When John Charles was twelve, the family moved from Ellerslie to another farm called Riverton on the other side of Wagram. The community bordered the Lumber River. John Charles started his formal schooling at Richmond Academy, later Spring Hill. In September 1894, John Charles McNeill entered Wake Forest College as a freshman. Here his ability gained quick recognition; he won the Dixon medal for the best essay his first year, and was appointed a tutor in English while still a freshman.

The year after graduation, McNeill went to Mercer University at Macon, Georgia, to teach English grammar and composition. The struggle to guide unwilling freshmen through the intricacies of syntax must have been a dull and irksome task for a youthful poet with a head full

of dreams.

Teaching did not however yield sufficient satisfaction for him to choose it as a profession. In 1900 he put out his shingle in Lumberton, over on the east bank of the Lumber River in Robeson County.

The practice of law in a small North Carolina town did not offer great variety or much of a challenge; nor did John Charles McNeill give himself up to it with any notable industry. The spell of the river extended to the very door of his office; the mysterious and enticing smells of the woods floated among his law books, and wild bird calls summoned him to explore. Clients often found the office locked because he had gone fishing. Naturally his practice did not flourish, but after his own fashion he was preserving his soul. Fishing expeditions meant also the storing up of images and observations which could be used later in poems.

While in Lumberton, McNeill bought an interest in a newspaper, the Argus, for which he wrote occasional editorials. When requested to do so, he happily wrote a brief county history to be included in the Dictionary of Robeson County (1900). In 1902 he sold his interest in the paper and returned to his native county, Scotland, where he formed a law partnership with Angus McLean in Laurinburg. During this period, he won an election to the State Legislature as a representative from Scotland County, and served a term in Raleigh. This political experience left little or no trace in his writing, except perhaps in his ability to cover political gatherings when he later worked for the Observer in Charlotte. Among the many local bills, he introduced was one to prohibit the sale of liquor in Scotland County and another to “prohibit the sale of fire-crackers more than three inches long.”

Meanwhile, he was pursuing his love of poetry. “Barefooted” appeared on 6 June 1901 in the Youth’s Companion, one of the nation’s most popular periodicals. Between January 1902 and December 1905, the prestigious Century Magazine used eighteen of McNeill’s poems, both lyrics and dialect verses.

In Charlotte, editor Joseph P. Caldwell of the Observer, a man of humor and ability, was searching for a feature-story writer to succeed Isaac Ervin Avery, recently deceased. When in the summer of 1904 H. E. C. (Red Buck) Bryant, a traveling representative of the Observer, called on McNeill in Laurinburg, McNeill admitted he was ready to leave the law profession; and after an interview in Charlotte, Caldwell hired him. Immediately McNeill started sending in copy to the Observer, though he did not officially join the staff until 1 Sept. 1904. Caldwell specified no definite duties. McNeill was to write whatever and whenever he wished; if he turned in no copy, Caldwell would understand. For the next three years, the editor’s faith in McNeill was amply rewarded. True, his columns came out irregularly, often on successive days, then nothing appeared for weeks. His columns had various titles: among them, “From Street and Lobby,” “Little Essays,” “Sunday Observations,” and “Unclassified Stunts.” He first used the heading “Songs Merry and Sad” on 2 October.

On October 19, 1905 the Patterson Cup, the first literary trophy in North Carolina, was awarded McNeill for a manuscript of poems published later as Songs Merry and Sad (1906). The award had just been established by Mrs. Lindsay Patterson in honor of her father, William Houston Patterson. President Theodore Roosevelt, at that time touring the State, made the presentation for the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association at the annual meeting of that body in Raleigh.

McNeill’s reply to the President after he presented the award “Mr. President, my joy in this golden trophy is heightened by the fortune which permits me to take it from the hand of the foremost citizen of the world. To you, sir, to Mrs. Lindsay Patterson, our gracious matron of

letters, and to the committee of scholars whose judgment was kind to me, all thanks.” Immediately after receiving the cup, he took the first train home to Scotland County to show it to his mother.

On the occasion of this award, J. P. Caldwell of the Observer, bursting with pride in the poet whom he had sponsored, wrote “Mark you, masters, — and this may be said without danger of turning his hard-Scotch head, — the man is a genius. The only fear concerning him is that North Carolina cannot hold him.”

There seems little doubt that the three years during which he worked for the Observer were among the happiest, and certainly they were the most productive, of McNeill’s life as a writer. To the rural McNeill, Charlotte seemed like a metropolis, and he was always delighted with the throngs coming and going. Yet his mind was never far away from Riverton, and when he occasionally disappeared, even during a busy time at the Observer, everyone knew he had gone for a while to walk the banks of the Lumber River. In the summer of 1907, he became ill and went to Wrightsville Beach in hopes of regaining his strength. When his condition worsened, he left his work and retreated to Riverton. On October 17, 1907 in his large room on the second floor of his parents’ home, he died of what was diagnosed as pernicious anemia. He was buried in the family plot at Spring Hill Cemetery. On the tombstone were engraved lines from his “Sundown” and the designation “Poet Laureate of North Carolina,” an unofficial title tendered him after he received the Patterson Cup. This period of activity was brought to an abrupt close by illness, which gradually increased until early in 1907 when he had to give up and go home to rest.

Sundown

Hills, wrapped in gray, standing along the west;

Clouds, dimly lighted, gathering slowly;

The star of peace at watch above the crest —

Oh, holy, holy, holy!

We know, O Lord, so little what is best;

Wingless, we move so lowly;

But in thy calm all-knowledge let us rest —

Oh, holy, holy, holy!

Lee M. White, editor of Wake Forest Student Vol. XXVII December 1907 No. 4 wrote “the death of Mr. McNeill, North Carolina and the South has lost one of her most brilliant men of letters. The “Robert Burns of the Old North State” is with us no more. Every lover of the beautiful, of poetry, of nature, feels his loss keenly, for his pen.”

Sunburnt Boys

Down on the Lumbee river

Where the eddies ripple cool

Your boat, I know, glides stealthily

About some shady pool.

The summer’s heats have lulled asleep

The fish-hawk’s chattering noise,

And all the swamp lies hushed about

You sunburnt boys.

You see the minnow’s waves that rock

The cradled lily leaves.

From a far field some farmer’s song,

Singing among his sheaves,

Comes mellow to you where you sit,

Each man with boatman’s poise,

There, in the shimmering water lights,

You sunburnt boys.

I know your haunts: each gnarly bole

That guards the waterside,

Each tuft of flags and rushes where

The river reptiles hide,

Each dimpling nook wherein the bass

His eager life employs

Until he dies — the captive of

You sunburnt boys.

You will not — will you? — soon forget

When I was one of you,

Nor love me less that time has borne

My craft to currents new;

Nor shall I ever cease to share

Your hardships and your joys,

Robust, rough-spoken, gentle-hearted

Sunburnt boys!

The September 6, 1915 issue of The Robesonian talked about Lumberton photographer Miss Lilliam A. Ferguson publication illustrated booklet of “The Sunburnt Boys”. It stated that she photographed scenes around Riverton catching beyond a doubt the very scenes McNeill had in mind as he penned the lines. The booklet is a fitting tribute to the beautiful words of McNeill. McNeill’s childhood home, Ellerslie, was moved to the grounds of the former Spring Hill Academy and serves as a museum to his memory by the Richmond Temperance and Literary Society which was founded in 1853. The Society’s headquarters is a hexagonal building where the society members publicly avowed abstinence from strong drink, debated public issues, and shared views of the literature of the age.

The next time you stop to lose yourself in the dark waters of the Lumber River also take time to remember these writers who in putting pen to paper have preserved their love for our great river.