Dark Waters of the Lumber River Bring Pleasure

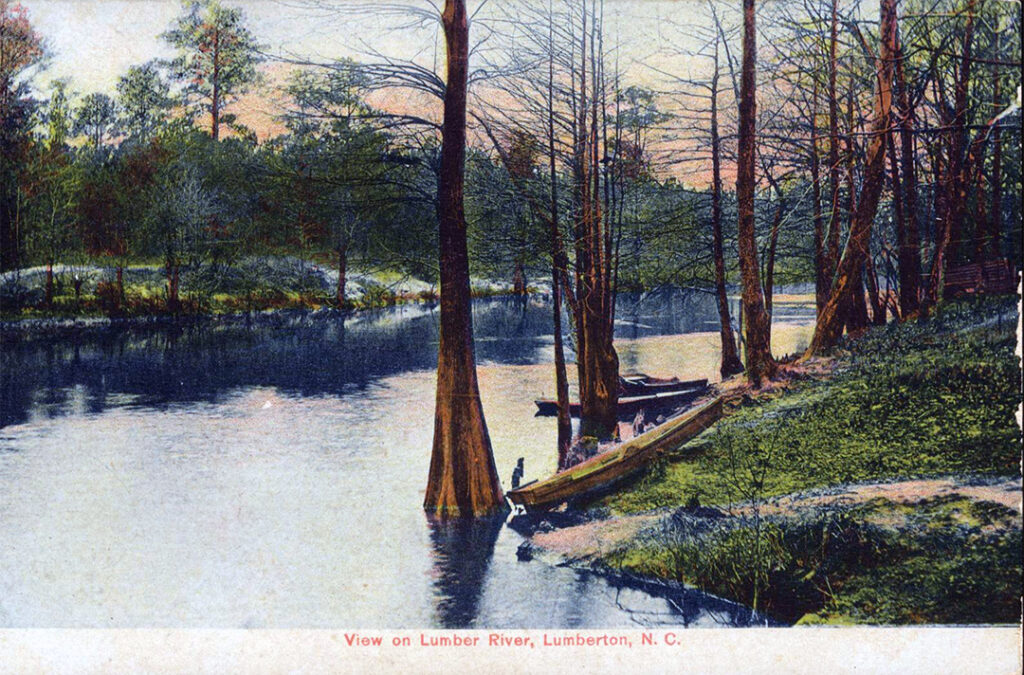

The dark swift waters that wind through southern North Carolina like a black velvet ribbon have gone by many names – Lumbee, Drowning Creek and the Lumber River. It travels from Scotland and Hoke counties into Robeson and Columbus counties before merging into the Pee Dee River.

At one time, the Lumber River served as one of the main thoroughfares for those living along its shores. It also served as a source of commerce and entertainment for generations. The Robesonian’s 1951 historic issue tells us that except for the courthouse, all of the early Lumberton buildings were along what is now known as Water Street, which was in the early days of the town known as the Wharf. There was a hotel, warehouses and a few stores that sold everything from silk to whiskey. Older folks told that in most any store you could find a whiskey barrel alongside the sugar barrel. The store keeper would draw a pint of whiskey and then grab a handful of sugar to mellow the liquor.

Fishing

The banks and waters of the Lumber River have called out as a siren luring young and old to come to the dark waters, fishing pole in hand, so that they might bring out the bounty of fish the river has to offer.

The Fayetteville News June 9, 1868, issue notes a letter that the reporter received from his brother in Lumberton giving glowing accounts of fishing in the river. He was able to fish just a few feet from the door of his store and was catching hundreds of yellow perch weighing from 16 to 24 ounces. The reporter stated if he had known of a store like that that was up for rent, he would have rented it for the term of his natural life at any price.

The Wilmington Morning Star provided lots of coverage of Robeson County, and it printed on April 27, 1876, that a report had been received from The Robesonian that, “Fishing season is now in all its glory and the fishermen are out early and late with the pole and line. The red breast, goggle-eye, blue brim and raccoon perch understand their business and lay hold of the hook with the most accommodating avidity. The tables of Robeson’s citizens are supplied with the most delicious of fresh water fish.”

In January 1, 1878, the Morning Star recounted the story of Dr. Richard Montgomery Norment, well known Robeson County politician. The doctor was fishing on the Lumber River when he lost a valuable gold ring overboard. He knew that with the deep water and soft, muddy bottom, there was no chance of retrieving the ring. Nine weeks later he was fishing in the same spot and caught a large trout. Later at home, he was preparing the fish to cook when in the stomach he found his ring that was lost for two months.

The April 2, 1881, Morning Star told of an attempt to protect the fish of the Lumber River in Robeson and Columbus counties. It became a misdemeanor to take fish from the river between March 1st and November 1st by any means other than hook and line.

Lumberton Postmaster Gordan Cashwell for many years wrote an article called “Then and Now” which covered not only current affairs but recounted his memories of Lumberton through the years. One of his stories talks about one occasion of fishing that led to an appearance in court of one of Lumberton’s favorite citizens. In November 1946, Captain Bill Bullard, who spent most of his life fishing the Lumber River, was caught by a game warden breaking the gaming law by catching fish in a trap. He appeared before District Recorder Robert E. Floyd for trial. He was represented by Malcolm Seawell, a promising young lawyer who later became North Carolina Attorney General. He was a fishing buddy of Captain Bullard. Seawell knew the Captain was guilty and that the law was irrevocable. He instructed his client to plead “Not Guilty,” and to trust that he would provide an emotional speech that would end in a pronouncement of “Not Guilty.”

These are some excerpts from the Seawell’s speech:

“Your Honor: Captain Bill Bullard has fished the Lumber River for sixty-odd years. Thirty years before Your Honor and I were born he was taking fish from the dark waters. He is the last of a procession of fishermen whose ghosts were haunting the cypress boles and the eddies from McNeill’s Bridge to Winyah Bay. When Captain Bill started fishing there were no laws to say when, where and how a man might take a fish. In these ‘dead days beyond recall’ the fishermen could use dynamite, nets and deadheads. He talks to the river and it responds. They speak with voices which we cannot hear, but which they understand. Captain Bill is the most colorful figure this town has ever known. It will never see his like again. He has little of this world’s goods. And yet, he is richer by far than the richest man who has ever trod our streets. Captain Bill knew John Charles McNeill, the John Charles McNeill, the image of the Lumbee. He knew those ‘sunburt boys (now grown old) of whom the poet sang.’ Over the years have emerged a thousand stories about the Captain. He knows the great and near great, the rich and influential, and knows them well, but the friendship of the humblest citizen means more the Captain Bill. If you find Captain Bill guilty you must sentence him. That sentence may be a fine, or imprisonment and the revocation of his fishing license. “Revocation of his license? It would be better to send him to the roads.” How can Captain Bill live without fishing? — Fishing is his life. His life is fishing. The Almighty gave us the river and its fish. He gave them to Captain Bill. He never placed restrictions upon the manner in which the descendants of Adam could take a fish. I do not know what Captain Bill’s religion is. Sometimes I believe that he, in his own way, is more devout than any of us. He has learned well the commandment, “Love thy neighbor.” The river has been good to Captain Bill. He has not mistreated the river. How could he defile that companion of his? Your Honor, if you or I or anyone of us were sick and needed a succulent red-breast or bass to tickle a jaded palate, Captain Bill would get in his boat, come hell or high water, and bring us the fish. Where or how he may have acquired it, we would not know, and we would not ask. Often at daybreak or sunset, Captain Bill has paddled me upstream in that flat bottom boat. Whether we caught us a string or returned empty-handed was of little concern to us. We do not know what the future holds for us, nor for Captain Bill, but I can hope that in the hereafter, the Styx may be the Lumbee, and Captain Bill it’s Charon- – – waiting in his flat bottom boat at daybreak to take me to the river’s bend.”

In a footnote to the copy of Seawell’s record of his speech, he wrote the following:

“The verdict was “Not Guilty.” Captain Bill was a bit on the deaf side and did not hear the verdict. I took him by the arm and led him from the courtroom to the conference room. Captain Bill said, “Boy, what did he say? I said, he said you were not guilty.” Captain Bill said, “Well, I will be damned.” Captain Bill Bullard died June 1, 1953.

Swimming Places

Cashwell wrote on August 4, 1971 about swimming during his childhood:

“The only swimming facility was Lumber River where the water was less contaminated than it is today. Many old timers will remember McMillan Beach, Hecks, Rock Bottom, and Cypress in The Middle as being favorite spots where they went swimming. Not many present day Lumbertonians are aware of the fact that approximately 60 years ago, our town for a few years enjoyed a distinction it does not now have, and which few towns had at that time. The distinction came when our town commissioners about 1911, made provision for a municipally owned and operated swimming pool by the conversion of an existing reservoir of cement construction and possibly 20 by 30 feet in size for use as a pool. It was a part of the light and water plant then operated by the town and was located at the site of the present water plant at a point about due west of the dead end of West 6th Street. Its water supply was raw water pumped from the river by steam operated pumps. It had a roof, probably to keep leaves from nearby trees from falling into it, and the side walls above the cement were louvered to keep out the leaves and to give privacy to the bathers. A narrow wooden platform was provided around the edges of the pool and a dressing room was constructed.

“My recollection which is shared by several people who were then youngsters, is that the pool was provided for girls only. The girls wore the flowing bathing suits of that day which contained so much cloth, it must have been different to swim in them.

“Boys had a choice of several places where they went swimming in the river in the nude, by shedding their clothes on the river bank. Often when after a swim, they prepared to dress, they found that some of their devilish companions had tied their clothes into knots.

“Abi’s cove, several hundred yards below the railroad bridge, and the upper sand bar, now known as McMillan’s beach were used mostly by beginners and non-swimmers as the sand bars provided shallow water. “Rock Bottom,” which was located near the present junction of Jenkins Street and Riverside Drive was comparatively deep and was used by those who were good swimmers.

“Heck’s Swimming Hole,” located further up the river at a point near the old Goat Club, or the Mrs. S.S. Small residence was another favorite place used by swimmers desiring deep water. These places provided privacy for the nude bathers, as the area between the Carthage Road and the river was an undeveloped open field and woodland.”

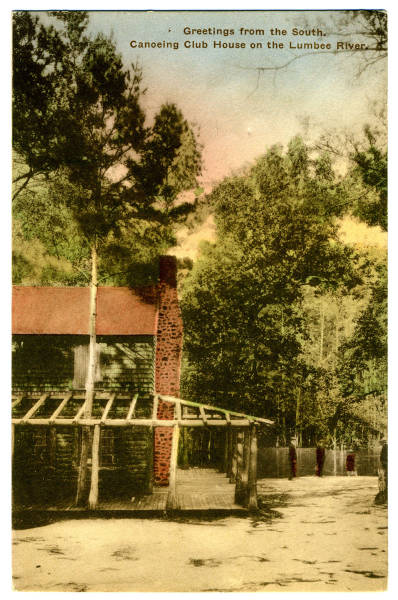

The Charlotte Observer’s August 12, 1916, edition communicated that the Maxton Beach on the Lumber River for weeks had been victim to North Carolina’s Great Flood of 1916. The Observer reported that when the flood waters began to subside, “Once again young people will be having daily picnics on its banks, others will be swimming. Some will just be enjoying the refreshing coolness of the beautiful clear water stream and sandy bottom. Sportsmen will be coming out with canoes and spend months fishing in the waters full of trout, bream, red breast and jackfish abound.”

Jennings’ and McMillan’s Beach

The first mention of Jennings’ Beach that I found was in the May 20, 1917, issue of the Wilmington Morning Star in which the writer tells about accompanying G.E. Rancke, Jr., to Jennings Beach located 2 miles west of Lumberton on the Lumber River. It was managed by his father G.E. Rancke, Sr., who advertised it as “the pleasures of the seaside at home.”

Rancke advertised in 1918 that he had adult and children bathing suits for rent as well as candies for sale. That year, he also offered to donate half of the proceeds of the busiest day during the next three weeks to the Red Cross. In 1921, he was alone at the beach when he became sick and knew that the only way he could get to town was to lay in a boat and let it float to downtown. He was 86 at the time. In 1922, E.L. Whaley and John G. Proctor, Jr., swam the 3 miles from the beach to the Sixth Street Bridge in an hour and 10 minutes.

The July 6, 1933, Robesonian told that Jennings’ Beach was renamed McMillan’s Beach. In 1934, there was an advertisement for the site stating the charges for the season. The cost for admission was ten cents. If you planned to use the bathhouse, the cost increased to fifteen cents. For twenty-five cents, you got admission, the use of the bathhouse, and the rental of a wool bathing suit. The ad also talked about season passes being available and that the site was well lighted for night swimming. The manager of the property at that time was Frank A. Wishart.

Over time, improvements were made to the site, including adding a playground and recreation building. The building housed a juke box and was used for dances and roller skating. The building was destroyed by fire in October 1967, and the entire site was closed around 1978.

In June 2000, Lula Williams gathered memories of McMillan’s Beach for an article for “Robeson Remembers,” a writing project of the Robeson County History Museum.

Williams said, “McMillan’s Beach was a landmark in Lumberton for several generations—in fact, it was the only place to swim and where most youngun’s learned how to swim from before the turn of the century to the ‘50s it had a dance pavilion and was a popular place for dates to go to dance to the jukebox fed by many nickels. Then and earlier, there was a bathhouse where one could rent a basket to store clothes while swimming and a canteen where all kinds of snacks, soft drinks, ice cream and other goodies were available.

“Crossing the river at the upper end of the beach was a bridge with a platform underneath and a ladder going down from the bridge to the platform. Erwin Williams Jr. remembered that you could dive from the platform or if you were really brave, you could dive from the bridge, but you had better have made sure that the river wasn’t low or the water wouldn’t be deep enough!

“The Boone family lived in the turn of the road just before you got to the beach. That’s why the part of the water with the deep water just above the main beach was called “Little Boone.” There was a huge tree on the far side of the river that had a long rope hanging down from the upper limbs and daredevils used to climb up and swing across the river on the rope and drop down into the deep black water. Great fun!”

Frances Caldwell Dietzel loves to tell the following story about a happening on the Lumber River a little further downriver from McMillan’s Beach: “It seems that years ago it snowed in Lumberton and the only hill around was in the back of Frances’ house on Caldwell Street. A number of the then-younger set gathered there to slide down the hill in the snow—two of the group had real sleds and everybody took turns. One named James McLeod (better known as “Bummy”) didn’t make the turn at the bottom of the hill in time and ended up in the river—clothes and all! He says that there was ice right at the edge of the bank! He had on big boots and a heavy coat and when he managed to get out of the river, his pants were frozen solid in under one minute!

“The group took Bummy into the house to dry off in the bathroom in front of an old-time round oil heater with the wick in the bottom—remember? He borrowed a pair of Mr. Mike’s long johns while he waited for Bobby Lewis to run down three blocks to Bummy’s house on Chestnut Street to get him some dry clothes. “Don’t think Bummy has ever lived this one down! In truth, it’s probably a miracle he made it out of the river at all.

“Some others in the group were Sim Caldwell and Torry and Kenneth McLean. Kenneth remembers a really big snow in March of 1927 that was six inches deep with ice. He says everything in Lumberton came to a screeching halt except for kids playing in the snow and being pulled down Main Street behind Mr. John Fuller’s early model car! Kenneth and Bummy think the close call Bummy had was a few years later than this.”

Jackie Oliver Utz recalls that Bunk Stone and her brother, John Hal Oliver, once caught an injured small alligator in Lumber River and brought him home. “They said the alligator had been shot. “He stayed in the dog house until my mother and I couldn’t stand it anymore! I was afraid to go out the back door.”

Jackie continues, “Bunk, John Hal, Clarence Townsend and Stanley Meares spent many hours in small rowboats wandering up and down the river. Often, they found sharks’ teeth and seashells along the banks when the river was low.

“It’s hard to believe when you see the river today, but my friend, Kitty Edens, and her cousin, David Edens, swam down the river from McMillan’s Beach to the area now known as Stephens Park. That was a dangerous and daring thing to do. A crowd of us anxiously awaited their arrival at the end.”

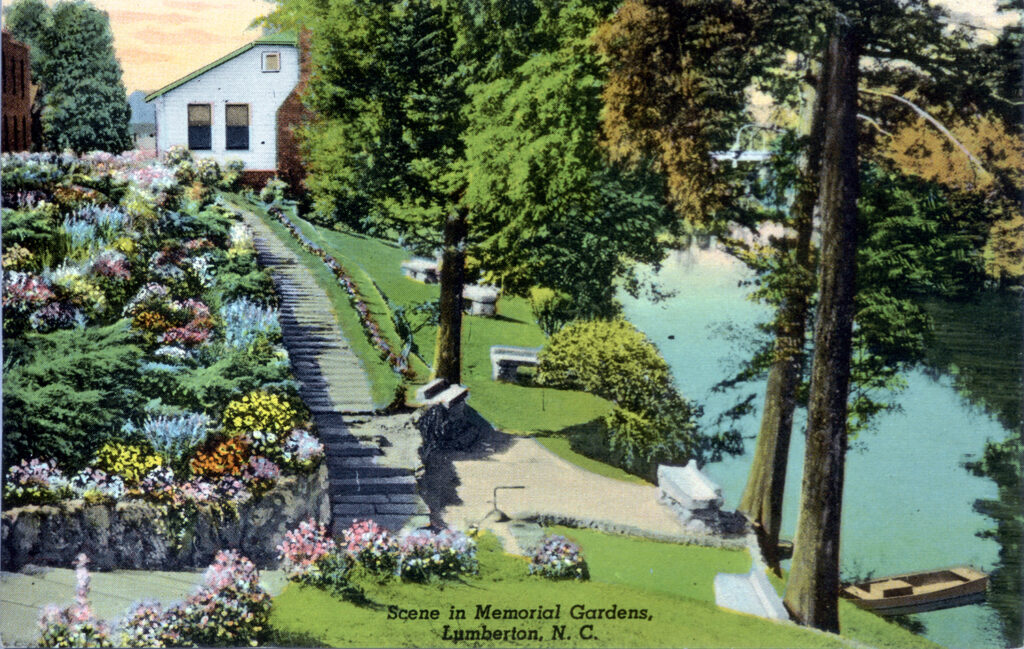

Riverside Garden

Mrs. Annie Caldwell Baker, wife of Dr. Horace Baker, Sr., had two great loves that were instilled in her by her mother, Dovie Carlyle Caldwell: flowers and downtown Lumberton. Mrs. Caldwell establish a sunken garden at her home on the corner of Elm Street and Elizabethtown Road. Mrs. Baker continued to nourish the garden, which was the talk of downtown Lumberton

Her own garden was not the only place Mrs. Baker planted and cared for flowers. An article in the April 3, 1939, issue of The Robesonian announced that Mrs. Baker and her good friend, Kate Britt Biggs, were to serve as supervisors of the riverside beautification project. The project established a garden along the banks of the river between the Fifth Street bridge and the American Legion building. The labor for the project was provided by the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide replacement jobs for those out of work due to the Great Depression. Mrs. Biggs stated, “We want anything from privet hedges to petunias.” The gardens served not only as a wonderful setting for a picnic, but as a place for those working downtown to get away from their busy work day to sit for a few minutes by the dark waters of the river surrounded by beauty. Sadly, nothing of the old garden survives except faded postcards.

McLean Castle

Mrs. Margaret French McLean, widow of former North Carolina Governor Angus Wilton McLean, in the late 1930s desired a place where she could entertain in a more casual atmosphere. Her Lumberton home on Chestnut Street known as Duart House was a very formal home. Her answer was to build a home on an eight-acre tract along the Lumber River that was once part of the National Cotton Mill property in West Lumberton. She chose German-born stone mason Christian Meyer, who came to America in 1905 and became naturalized in 1929. In October 1939, he arrived in Lumberton and worked at the St. Frances de Sale Catholic Church building a retaining wall along the Fifth Street side of the property. The wall was concrete and built to look like logs. It served as a flowerbox. He married Janie Edmund, daughter of Ellen Tyson and William O. Edmund. He was 50 at the time he married 29-year-old Janie, a waitress at Carolina Café. The couple lived with her mother and siblings on Old Whiteville Road.

Meyer then began work on what has become known as “McLean Castle”. The home has the appearance of a Bavarian mountain home but was constructed completely of cast concrete. The home was built directly on the edge of the river bank with windows overlooking not only the dark waters but also out into the gardens of the property. The inside of the house carried out the same log design as the outside. The partial wall that separated the main living area of the house featured concrete trees with the appearance that their upstretched branches were holding up the roof. The room also featured a large fireplace. Meyer’s design for the grounds included a maid’s quarters behind the main house and a gazebo. There were small canals dug throughout the gardens to let water flow under the oyster shell and concrete bridge. He also designed concrete planters that looked like tree stumps and an old fashioned covered wishing well.

Things were not always good for this German immigrant as the sentiments around the world turned against Germany after its invasion of Poland. The July 10, 1940, issue of The Robesonian reported that rumors that were spreading all over Lumberton about Meyer. They included that he had been spirited away to Fort Bragg and forced to reveal his possession of extensive maps of Lumberton and Fort Bragg, leading people to think that he was a German spy and was studying where the area might be vulnerable. Fort Bragg officials, as well as Meyer’s co-workers, all proclaimed the rumors as false.

The McLean family used the castle property for many years to entertain and Mrs. McLean’s oldest son Wilton actually lived in the home for a while. Her son, Hector, used the property to host parties for his employees at the Southern National Bank before the river side retreat was sold outside the family. The current owner, John Cox, grew up near the castle and his family farmed near McMillan’s Beach. He is working on preserving this unique Robeson County landmark.

River Secrets

In 2000, Paul Valenti, a local scuba diver and historian, said “The murky water of the Lumber River hides more than catfish and eels. In certain sections of the river—in low water conditions—fossilized remains from prehistoric mammals and sharks, along with a wide variety of other sea life, can be found exposed along its banks. These remains date back to the Miocene epoch period around 5 to 10 million years ago when the region was covered by the ocean.

“One area in particular (around Stephens Park) contains some of these fossilized remains, along with the remnants of a grist mill owned by German immigrants named Wessel. This mill operated in the 1800s. The mill was in the bend of the river to harness some of the power of the river. In extremely low water conditions some of the holes for the pilings are exposed. While diving in the area, a few bottles and some broken china was found.

“In May 1985 the Lumber River revealed one of its greatest secrets – a canoe dating back to 930 A.D. The 16.6-foot canoe made from yellow pine was pulled from the dark river waters near McNeill’s Bridge. The canoe was burned and scraped by Native Americans of the area to be used for transportation along the river.

“I was actually diving in search of other objects and I really wasn’t sure just what it was. it was wedged up against some trees and other debris, so it wasn’t easy to recognize. He decided it was an Indian artifact and marked the area so that he could bring archaeologist back to examine the canoe.”

The North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources confirmed that the canoe was the oldest found in the state, dating back hundreds of years before the 1700s Lake Waccamaw canoe that had been the oldest one on record. The canoe has been preserved and is housed at the Native America Resource Center at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

Dr. Linda Oxendine, former Chair of the American Indian Studies department and Director of the Native America Resource Center at the UNCP, told me that the men transporting the canoe to be restored told her, “As we drove the trailer out of the boundaries of Robeson County, bits of the canoe started flying off like it didn’t want to leave its home.”

I urge you to take time to paddle a canoe on the dark waters, grab a pole and fish from the tree-lined banks or just sit and drink in the beauty and peacefulness of the Lumber River and its surroundings.

Writer’s notes: I drew much of the information for this article from vintage newspapers.