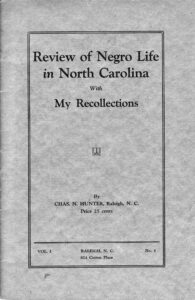

{Writer’s Note: Retold from Hunter’s words as found in his book “Negro Life in North Carolina with My Recollections”.}

While doing some research in Duke University’s archives, I stumbled across a mention of Charles Norfleet Hunter’s teaching in Shoe Heel (modern day Maxton). Pouring over the letters, scrapbooks and newspaper articles in the Charles N. Hunter Collection, I began to discover the important role that Hunter played in the early education of African Americans in North Carolina.

Early Life and Education

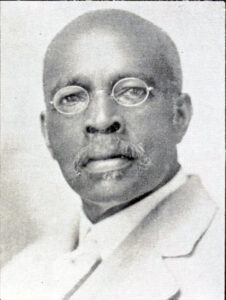

Hunter was born 1851 in Raleigh to slave parents, Osborne Hunter, Sr. and Mary Hunter. His father, a member of the slave artisan class, was trained as a carpenter, wheelwright and miller. Osborne was the property of William Dallas Haywood, Mayor of Raleigh before and after the Civil War and Vice President of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. Charles’ parents, like many slaves, were not allowed to marry, and in fact his father actually leased his mother from her owner. The couple maintained a household at the corner of Jones and Dawson streets.

Following his mother’s death when he was four, Charles and his siblings were moved into the Haywood household where his aunt served as nurse to the Haywood children.

Charles wrote later in life of his closeness with the Haywood family and how they considered their slaves part of the family and not just human property. Close relationships between owners and slaves were not unheard of in North Carolina, with examples of such friendships lasting into the 20th century. Hunter remained close to the Haywoods, often turning to them for assistance and advice. He credited much of his success to his years spent with their family. Citing the Biblical words of Ruth to Naomi, “Thy people shall be my people and thy God my God”.

At the end of the Civil War, the free blacks were left to make lives for themselves and their families. Hunter saw education as a tool to create a new world for the former slaves. He first pursued his own education and was valedictorian of his class at Raleigh’s Johnson Normal School. He attended Shaw University for a year. He was hired while still in his teens as assistant cashier of the Raleigh branch of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company.

Hunter the Educator

Hunter learned from Rev. W.W. Morgan that there was an immediate need for a Negro teacher who could pass the examination of the Robeson County School Board. Several had been tested and failed. In 1875, the county had only 4 licensed Negro teachers.

In Hunter’s book “Negro Life in North Carolina with My Recollections,” he chronicles his fifty years of educational work. Hunter describes his trip to Shoe Heel and his life in the newly incorporated town.

In December of 1875, Hunter left Raleigh for Shoe Heel by train to Jonesboro and then on to Fayetteville. In Fayetteville, he met Lumberton resident, Col. Neill Archibald McLean, Sr. McLean climbed in the coach for Lumberton and the driver told Hunter to sit up top with him. McLean stated he wanted Hunter to ride inside with him so that they could keep each other warm. McLean wrapped himself and Hunter in a borrowed blanket to fend off the cold.

The coach traveled 11 miles, then stopping for a change of horses at a shanty. After the next 11 miles, it was time for another change of horses, this time at a cottage. The driver invited McLean in for a cup of coffee. McLean invited Hunter to join them inside. Hunter remembers that McLean drank the coffee while Hunter stood at the fire warming himself. “0, how I did want just a swallow of that coffee!” But sadly, it was not to be.

The coach entered the swamps with large trees creating walls around them. McLean questioned Hunter about his background. McLean was pleased with Hunter’s connection to the Haywood family, saying they were one of the oldest and best families in the State. “In this opinion I took immense pride for I felt that I shared the compliment which he so generously bestowed. Negroes in the old days claimed kinship with all the white people who were related to their owner.”

After a 45-minute train ride from Lumberton to Shoe Heel, Hunter was met by railroad porter, Mr. Sam Crump. Hunter was to make his home with the Crumps for the next three years.

Mrs. Crump was an excellent housekeeper, devout Christian lady and delightful hostess. Their two daughters, Sallie and Louise, completed the family. When first seeing the Crump home, Hunter was puzzled about where he was going to stay because the home consisted of only one room and a small shed room. “I was curious to know where I was to sleep.” At about 9:00 p.m., Mrs. Crump pulled a curtain around one of the beds to screen it and from under the other pulled a trundle bed.

Evenings were spent reading the Bible and singing old hymns. The Crumps were very religious. Hunter recalled that her prayer language was profound, and he was deeply religious but of nervous temperament, highly emotional and impulsive. “His whole heart went into his petitions. I have so often wished that every home in our land were such a Bethel as was this one.”

That first Saturday afternoon, Hunter spent time looking over the town. It had grown out of the swamps with no regular streets and the Carolina Central Railroad passed through the center of town. The businesses were on the west side of the tracks: E.L. McCormic, J.C. McCaskill, Dr. Croom’s Drug Store and B.F. McLean and Co. Hunter also found a number of comfortable private residences, a turpentine distillery, a cooperage and Lewis Lilly’s barbershop. Drainage ditches four to five feet deep ran along the outer edges of the sidewalks and in wet weather they were nearly full.

Hunter’s school opened on Monday in the Methodist Episcopal Church with a large number of students. He spoke of the children’s being neatly clad, respectful and well behaved. After the first month, he returned to Lumberton before the Board of Examiners to draw his salary. The Board consisted of W.B. Blake, J.A. McAllister and a Mr. McIntyre. Teacher’s pay rates were based on the level of certificate that the Board awarded. The certificates ranged from a first-grade certificate with the highest pay rate down to the lowest pay rate for a fifth-grade certificate.

“I held a first grade certificate in Wake although I had never taught. Imagine my surprise when they awarded me a third grade. I was disappointed. I was discouraged. I would have thrown up the job and left were it not for the fact that I did not have money to get home.”

Hunter did manage to make it home to Shoe Heel. He then called a meeting of the School Committee and explained the situation. Mr. Bishop, the white member of the Committee, said, “Hunter, I know you are qualified. I have visited your school and have seen and heard you work. We intend to keep you and it is the sense of the Committee that the deficiency in your salary be made up by voluntary contributions.” After another month, the Board awarded him a second-grade certificate.

Hunter remained in charge of the school for three years. He talked of his pupils as a fine body of boys and girls:

“I loved them and they gave every evidence of full reciprocation of my affection. Their parents and community generally gave me hearty cooperation, none of them ever complaining.”

The pupils’ parents often took a day off from work and spent it in the school observing the work and behavior of their children. This gave parents a deeper sympathy with the teacher and their task. Hunter made a comment that resonates to this day:

“Would it not be well for parents to do so today the same? If they would follow the example of those Shoe Heel people is it not possible that much of the friction, discord and antagonism, which are destroying our schools almost everywhere, would be avoided?”

Hunter recalled that during those Shoe Heel years, he never received a single disrespectful look or word from any pupil. He reported that he “used the rod when necessary and no ugly spirit was ever shown”.

Hunter left Shoe Heel to become principal of the Garfield School in Raleigh. A testament to Hunter’s teaching ability is the fact that many parents sent their children to Raleigh to continue their studies under him. When the Shoe Heel children came to Raleigh, it was discovered that while they attended school only four months a year, that they were far advanced over those in Raleigh that attended ten months a year. Hunter commented, “I could then see what the high standard of scholarship for teachers adopted by the Examiners for Robeson County had done for the children of that county.”

Hunter ends his account of Robeson county life with a very interesting story that has a wonderful life application for us all:

“During my stay in Shoe Heel the surrounding country was very swampy and infested with snakes. I was awfully afraid of snakes. I was looking for them everywhere. If I heard a rustle in the leaves, I stopped and made an investigation and soon delivered a snake. If I heard a noise in the bushes I examined and found a snake. I think I saw more snakes than any one in Robeson County. Well, I was looking for snakes. Other people were not. I have drawn a lesson from this. It is ever so in life. If we are looking for the bad we will find it. If we are looking for the good we will find it. If we are looking for snakes we will surely find them.”

Hunter worked an additional 47 years in education, teaching in locations such as Oberlin School in Raleigh and the Booker T. Washington School at Wilson’s Mill. In 1890, he served as the Secretary of the North Carolina Industrial Association and was editor of its “Journal of Industry”. He also served as editor of the “Raleigh Independent” and “Our Advance”.

Charles Norfleet Hunter died on September 4, 1931, after a 3-month illness. Hunter was truly a remarkable man, a monument to self-determination and the power of education.